Exploring the Mysterious North East Corner of the Prom

Members of the Bayside Bushwalking Club took a walk on the wild side in March 2020, exploring the north-east corner of the Prom. Written by Paul Redmond.

The official ‘Park Notes’ for the Northern Section of Wilsons Promontory are quite discouraging. Walks’ Reports posted on the internet are not all that encouraging either.

This unlikely wilderness sits over there, across the flat country, to the east of the bitumen road to Tidal River. It beckons and tries to tempt the bushwalker with an inaudible siren call, “Turn your car into Five Mile Road and abandon that walk planned to commence at Telegraph Saddle”. We barely notice the grey/blue hills to the east. Your itinerant bushwalker remains aloof and never visits this mysterious north-east corner of the Prom.

Now, at long last, I have seen it first-hand and it is good.

The Northern Circuit is certainly not for the faint-hearted nor the unfit nor the unprepared. It is a hard walk done in long daily stages due to the distance between the relatively few campsites and the condition of the tracks. These remote camps are limited to six persons per night. There are limited assured water supplies and no Plan B optional routes. You are unlikely to meet anyone on the 60 km circuit. Some go clockwise others prefer the reverse. We went clockwise.

The majority of the circuit’s component tracks are overgrown and consequently hard to follow. You are pushing through dense scrub varying from knee-high to two metres and higher. There are numerous blind culs-de-sac caused by so many having gone astray at the same point, typically following a wombats’ runway, deviating around the prickles of Hakea or the points of a Xanthorrhoea or by just missing an unexpected right-angle turn. The tracks have more meanders than the Brisbane River. We lost the track quite often, but could quickly realise our error and recover, thanks mainly to the leader’s GPS or less technically, three pairs of eyes searching high and low for the elusive pink tapes that mark the true path of righteousness. These tapes vary from bright pink that contrasts clearly with the background, through to faded pale remnants that are hard to spot. New or old, they may be wrapped around a branch, high or low; flapping in the wind from a mere slip of a branch or tied to a juvenile trunk top that can barely support its own weight in the wind. You are never sure where to look.

The foot track, a narrow shallow groove in the ground, can be followed with care, but one cannot spend a whole trip staring at the ground. The scrub’s branches have grown over the track and they close ranks immediately behind the walker you are following, barely three metres in front. You can see where they are, but not how they got there. It was hard and tiring, constantly pushing through the scrub. Fortunately, most of the scrub we encountered had quite soft and flexible juvenile growth.

There is, however, plenty of resistant mature growth and hard deadwood with sharp broken ends to scratch an uncovered arm and sometimes draw blood on a covered arm with no damage to the protective sleeve. Compensating areas where the scrub is knee-high and not such hard work do exist, but even there the track can still be hard to follow. Being a wilderness area the signage is sparse; often old and faded.

Being a wilderness area the signage is sparse; often old and faded.

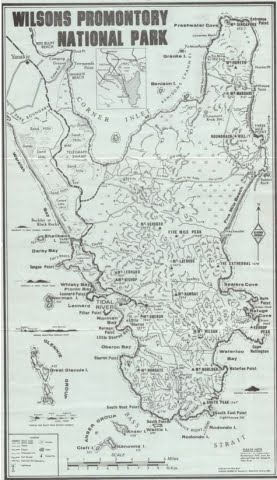

Five Mile Road is a closed Management Road that crosses the Prom running almost due east from near the southern reach of Corner Inlet. It is a tacit dividing line between the north and south sections of the Park. It is the way into and the way out of this wilderness.

We departed the car park on Five Mile Road at 1:30. The undulating gravel surface of the road eased us into the start of this expedition. The expansive views of Corner Inlet to our north-west (left) were revealed afresh at the top of each rise. Always in view is the scrubby flat country to the north-east which contains Chinamans Swamp and its marshy environs.

The undulation of the scrublands is relieved by many clumps of trees and small rises and typical Prom rocky outcrops. Mount Vereker (638m) and Five Mile Peak (475m) stay in view at the southern edge of the wilderness. Roundback Hill (314m), Mount Margaret (219) and Mount Hunter (348m) run to the north-east in a distant line. Mount Singapore (145m) is just visible at the northern tip of what J. Ros Garnet refers to as the Singapore Peninsula in his ‘History of Wilsons Promontory’.

Descending a small rise, we see a green Parks’ sign planted in the sandy runoff beside the road, standing authoritatively in front of the dense scrub. It proclaims “Lower Barry Creek 4.3km” and “Tin Mine Cove 18.9km” with each notation accompanied by a broad arrow pointing to the sky. Good so far; but where is this sign-posted track. There is not even the slightest gap in that wall of scrub to indicate the track into the wilderness. After much examination of the area, eagle eyes recognised a change in the patterns in the sand revealing where to part the scrub and step through the curtain onto the track. Talk about “What’s behind the Green Door?”

And so we were into it. Not quite the great unknown, but if the entrance is a guide, who knows what this afternoon may bring.

Two hours and twenty minutes (and 4.3 kms.) later, the party emerged from the scrub where the track crosses Barry Creek. A long stride across the leisurely flowing black tea coloured water, up the steep sandy bank and we were standing in the camp. When written down, the afternoon’s distance does not seem that much, but your author, for one, was very glad to reach the mysterious Lower Barry Creek Camp. I anticipated that this camp would be quite unlike the more familiar southern section camps that sprawl among the tea trees behind a beach. And it is; a small clearing hiding in the forest with just enough space to accommodate the regulation maximum of six walkers; in fewer tents.

Mid-morning on day two saw us crossing the infamous Chinamans Swamp. We were lucky. Most of the swamp that we transited was just damp, squashy or even dry. The three recognisable water courses that crossed our appointed way were knee-deep in opaque muddy water that just hovered over an unseen, very soft and uneven bottom. It seemed as if we were walking along the creeks, not crossing them. No luxury of boardwalks in the wilderness.

It could have been worse. Horror stories of seemingly endless waist-deep swampy sections, are told by the intrepid who have passed through in wetter seasons. I was elated when I realised that we had just stepped up from our last quagmire. I exaggerate. It was more muddy water than watery mud, with green ribbon-like weed growing in the water and floating languidly on the surface.

Having passed through the swamp, there was about one and a half hours through the difficult scrub to the southern end of Chinamans Long Beach. From the rises on the track we were treated to expansive views of the huge saucer which is drained by Chinamans Creek and Barry Creek into Corner Inlet. Track conditions gradually improved as we approached the beach, as scrub gave way to tea tree and the track surface gradually became sandy, indicating that the beach (and lunch) was not far ahead.

A gusty wind on the beach sent us back into the shelter of the foreshore tea tree for lunch. Anthony discovered Warragul Greens growing at our picnic spot, but no one moved to supplement their rations. A four kilometre walk on the wave compacted sand to the northern end of Chinamans Long Beach brought us to a track to take us above the rocks and the headland and around Tin Mine Hill to the Tin Mine Cove camp. We arrived at the respectable hour of three o’clock or thereabouts; this seemed to satisfy our leader’s desire for punctuality.

We braved the cold sea for a brief swim at the Tin Mine Cove beach. We could have used a swim yesterday afternoon at Lower Barry Creek Camp after the warm first afternoon.

The tracks pass through many sylvan patches of Banksia forest. A pleasure to pass through, to admire the gnarled old trees with bark-like hard old blue-grey leather, all splits and knobs They are such a contrast to the adjacent younger slimmer saplings, branching out abundantly with new growth displaying fresh green leaves. It is not all doom and gloom. There are sections of track that are easy to follow with no thorny flora, passively waiting to attack the labouring bushwalker.

Fortunately, the hills are gentle. The track, for all its shortcomings, has no replications of the long climb up to Telegraph Saddle or the knee destroying climb up to the Lighthouse precinct past the concrete helipad.

There were two precipitous descents on to beaches. If you had chosen the counter clockwise circuit, they would be very hard going as your feet slipped and sank into the loose sandy soil; handholds proving to be unattached to the soil, despite the appearance of security.

The scrub bashing was offset by two long beach walks – Chinamans Long Beach on the western side and Three Mile Beach on the eastern side. Beach walking is seen by some as boring, but there is pleasure in walking on a gently undulating beach, more or less in a straight line, except when searching for harder sand. I concede that a beach that slopes steeply from foreshore to waters’ edge is a pain in the downhill knee. If you are ambushed by a silent rogue wave as you walk the hard sand near the water’s edge, lost in a beachcombing reverie, it is a serious pain in the bottom. The beach sections were such a pleasant relief to the hard work pushing through the inland scrub with eyes constantly on the lookout for the next pink track marker and wary for reptiles basking on open sunny sections of track.

The track eastwards across the Prom, on day three, from Chinamans Long Beach to the lattice navigation light tower above Three Mile Beach was easy to follow for the most part. It had been cleared by Bushwalking Victoria volunteers about five years ago, but nature does not sit idle, another two to three years will see sections of the track all but disappear under the vigorous regrowth. Towards the middle of the crossing, a short length of the track is formed by an ancient corduroy surface. The logs forming the path are held in place by rusted steel cables secured to the logs by thin dog spikes. The substantial thick cables have deteriorated and parted from the logs whose charred ends showed that they had been burnt in a bushfire in years past. It is a relic of the bygone days when the track was formed for vehicles. Only a truck could have carried those cables to the site. Presumably, they were scavenged from the abandoned tin mine near Chinamans Beach (the short one north of Tin Mine Cove).

Day three included a brisk march along Three Mile Beach. Here, with their feet and trunks buried in the creamy coloured sand, the grey skeletons of large trees stand tall with an eerie starkness, against the green backdrop of the hills at the end of the beach. There are many reclining tree trunks lazing about, but they lack the gaunt starkness of the upright ghosts.

We lunched at the southern end of Three Mile Beach.

Between Three Mile Beach and Johnny Souey Cove the track skirts around Three Mile Point which rises above the waves crashing in from the Southern Ocean onto the granite boulders with their coating of the endemic orange lichen. We discovered the hard way that there is more than one track around or indeed, over Three Mile Point. The main track which is clear and well defined eluded us as we fell to the temptation, after lunch, to take the first indication of a track. We followed some intermittent and elusive fading pink tags, heading uphill on an abandoned track which deteriorated to “route only”, a term I first saw on Duncan Brookes’ VMTC maps of walking areas in the High Country.

What remained of the track eventually disappeared from under our feet, leaving us pointed uphill and nowhere to go. The GPS would have told us, had it come equipped with a voice, that we should have walked a few metres further around the beach after lunch to where we would have easily picked up the cleared track – the track that did not climb high over the hill, but followed the contour around just above of the rocks and the waves.

To recover our position without retracing our steps, we compromised between blindly progressing over the hill towards Johnny Souey Cove and dropping directly towards the crashing waves. We did this by taking an oblique route down through the scrub towards our destination. This action slowly progressed our journey and brought us to the elusive well defined cleared track and the resultant increase in pace.

We ‘passed’ on an inspection of the Johnny Souey Cove campsite and pressed on in the luxury of a good cleared track over the divide separating the two bays. From our vantage point, we could see several runabout boats in the lee of Rabbit Island as well as between Monkey Point and Rabbit Rock.

As Anthony remarked, “No doubt those fishermen are looking up at us and wondering why people would choose to walk those hills with a load on their backs”. “They could be sitting down like us with some luxuries and no effort involved when you wish to relocate to another place where the fish could be biting”.

The day finished with a precipitous drop into Five Mile Beach. Low tide meant we could rock hop across Miranda Creek with dry boots. Camp was just off the beach.

A spring emptying into Miranda Creek delivered the best water of the trip; very weak black tea. The flow at the spring was quite strong, but most of it was inaccessible under rocks. The small flow that was available to the thirsty bushwalker was efficiently directed into water bottles by means of a short flexible plastic tube carried by one of our number for such a purpose.

Another swim – very cold; very brief.

Fresh water was a potential problem for the entire trip and the advice had been to treat the second night’s camp at Tin Mine Cove as a dry camp; any potable water a bonus. We carried extra water for that camp, but it turned out that after Don filtered the local water, we had scored the bonus, even if there was a pronounced mineral taste to the water. Walk reports on the internet of trips early in 2020 gave mixed reports about the water supply at most campsites, but luckily we had no problems, apart from having to fight the undergrowth to get sufficiently upstream on Tin Mine Creek to reach the clearer faster-flowing water. Tin Mine Creek’s better water is not indicated by the coloured water lying limpidly across the beach, seeping into the sand and not quite reaching the water’s edge.

The campsites are small and there is a six-person per night limit. There are neither toilets nor the luxury of the piped water that constantly flows at the Sealers’, Waterloo or Refuge camps. Infuriatingly, toilet paper littered the outer perimeter of the camps; very disappointing. You would expect that the experienced walkers who venture into this wilderness area would be model citizens in the defecation department. Perhaps the boaties, who sometimes use the beachside camps, could be the culprits.

The weather, although mostly overcast, was kind to us.

From our vantage point at the Tin Mine Cove camp, in the afternoon and evening of day two, we could see rain showers heading across Corner Inlet from the southwest towards us. But for the most part, the rain moved around us, beyond our north-eastern side and we boiled our dinner water without resorting to parkas.

We were treated to overnight rain at the final camp at Five Mile Beach. Fortunately, we were able to dry our tents and pack up during a long break in the showers on the final morning. The weather on the westward walk across the Prom on the ‘management only’ Five Mile Track was showery for the most part. We three did not hesitate to bring out the pack covers, but there was no uniformity in the donning and removal of parkas as the intermittent showers of varying intensity, passed over us. Happily, the sun emerged for the last hour of that 18km crossing, so that we finished our journey warm and dry.

The author’s boots celebrated 11 years of existence and 125,000 kms of uncomplaining service with the sole separating from one boot and its companion trying to separate on the other boot. Fortunately, the toe end of the soles stayed put. Anthony did an excellent job of binding the sole at the instep with gaffer tape (without my having to remove the boot) and with the instep strap on my gaiters assisting, my boots made it to the end of the road.

We took four days, but effectively it was three days, and 60 kms. The Northern Circuit is a very hard walk.

It is immensely satisfying to complete a hard walk and see new country, particularly so, after you have recrossed the car park, deposited the pack and removed your boots from the weary feet at the bottom of your weary legs.

For beauty and coastal views, the North-Eastern corner of the Prom is the rather plain sibling of the overused Southern Section, but beauty is only skin deep. Don’t be discouraged, give some serious thought to this Cinderella and be pleasantly surprised.

Walkers:

| Don: | Leadership and Navigation |

| Anthony: | Morale and Botany |

| Paul: | Timekeeper – Rests and Lunchbreaks |

| Day 1 (afternoon): | Five Mile Track, Walking track to Lower Barry Creek Camp: | 11 km |

| Day 2: | Chinamans Swamp, Chinamans Long Beach to Tin Mine Cove camp: | 13 km |

| Day 3: | Cross the peninsula from Chinamans Long Beach to Three Mile Beach and Johnny Souey Cove and on to Five Mile Beach camp: | 18 km |

| Day 4 (morning): | Five Mile Track to Car Park: | 18 km |

Notes

1. The Algona Guides ‘Map of Wilsons Promontory’ 1972 (price 20 cents) (see below) shows the track across the Prom between Chinamans Long Beach and Three Mile Beach as a vehicle track. This ‘cross Prom road is shown connecting to the rest of the world by a north/south road down the centre of the Singapore Peninsula, to the existing Five Mile Beach Road. The north/south road is now closed, even as a walking track.

2. A History of Wilsons Promontory National Park

Published electronically by the Victorian National Parks Association, May 2009

http://historyofwilsonspromontory.wordpress.com

Comprising:

- An Account of the History and Natural History of Wilsons Promontory National Park, by J. Ros. Garnet AM.

- Wilsons Promontory – the war years 1939-1945, by Terry Synan.

- Wilsons Promontory National Park after 1945 [to 1998], by Daniel Catrice.

3. The Rise and Fall of the Mt Hunter Tin Mine – A History of Northern Wilsons Promontory – Ian McKellar, 1993

4. Algona Guide from 1972